It’s early December 2020 here on the plains of Nebraska and we’re just getting started with Muzzleloader season. Last night I was driving the short mile and a half home from my tree stand and I saw a deer on the side of the road. I slowed and favored the side of the road he was on with my high beams, he wasn’t running and didn’t appear to be too concerned with my truck. He was not acting like a normal deer acts this time of year. He stood there in my headlights then nervously began to step toward a tree line. That was when I realized that he was limping severely on his front leg. Three weeks prior – to the hour – I had helped the young man who had shot this deer, along with his father, track this exact deer shortly after he had been shot. We tracked him for well over a mile before losing the blood trail. While we were tracking him, I talked with the young man and his father about how the deer was shot, it’s orientation at the time of the shot, etc, etc. The young man told me that he had borrowed his older brother’s 243 Winchester because his brother was off at college and not using it….and he wasn’t sure what bullet he was shooting, and that the deer was broadside, and only about 15 yards away, so there was just no way he could have possibly missed… I had a pretty good idea what had happened at this point…

My mind snapped back to December of 2019. One year to the month prior. The owner of the neighboring tract of land to the east, stopped and asked me, in as an accusatory tone as an extremely polite Nebraska farmer can ask, “if I’d have happened to have wounded a deer while I was hunting.” He went on to tell me, “that they were trying to get a wounded buck down that was on their property and, would I want to help?” Which is how a very polite Nebraska farmer says – “I am fairly certain that you wounded this deer, you inept SOB, and you’re coming with us and putting your tag on it when we get it down.” I politely obliged and after a rodeo of a hunt, I killed the deer for them and punched my muzzleloader tag and hauled him off. They’ve yet to invite me hunting again, which serves edify my position on the nature of the initial invitation to hunt with them. It also makes me grin on the inside, also being a polite Nebraskan, in the agrarian line of work, knowing very well that the only deer that I had shot during the current season were in my freezer already. It became fairly obvious that we had someone else hunting in our area and wounding deer. The deer in question had been shot in the front leg, just below the body level some time prior as the infection was severe. Just like the deer that was currently standing in my headlights. The bullet had not exited the leg intact. It almost certainly had to have been a small, high velocity varmint bullet. The same farmer later contacted me about the 3rd wounded deer…asking if I knew anything…he didn’t seem surprised to hear that it was wounded by a young hunter with a 243 Winchester.

If this weren’t enough, yet another year prior, in 2018, this time the second weekend of Nebraska rifle deer season in late November – less than 1/4 mile to the west of the exact spot where I now sat watching the 3rd gravely wounded buck in 3 consecutive seasons limping toward a bedding area – I had killed a 3rd wounded buck. This one was sporting a very poorly placed “Texas heart shot” that had shattered his left hip and left him crippled. After inspection of the wound revealed telltale fragments of thin bullet jacket and only about 6” of penetration, it was undoubtedly a wound made by a very high velocity cartridge with a light jacketed bullet.

3 years and 3 wounded bucks. All 3 young bucks that really shouldn’t even be getting shot at anyway – in my opinion. While I can only speculate on the first two deer that required a coup de gras after they had been shot initially, the 3rd deer, I know exactly what happened. Rookie hunter, in a tree stand at very short range – high angle shot – with a cartridge that is marginal deer hunting in the first place. What wounded this deer was “tolerance stack”. Too many variables that added up to the young hunter failing to cleanly kill the deer at which he was shooting. The hunter shot the deer low in the leg. Between that high angle of the shot, (the deer’s close proximity amplified the angle created by the elevation of the tree stand) and the height of his scope over the bore of the rifle is also amplified by the very short distance to the target; the physics of the situation in combination with a lack of experience led to a wounded deer. Had the young hunter been shooting a 6.5 Creedmoor, 6.5×55, 270, 308, 30-06, etc, etc…it is much more likely that both legs would have been broken and while it would have been an uncomfortable experience for both hunter and the deer, the outcome would have likely been different as there is a much better chance he’d have broken both front legs…

Wounded deer – wounded game animals in general – are inexcusable…but it happens. Biggest single factor effecting wounded animals?? Shot placement. What is worse than poor shot placement? Poor shot placement with a cartridge that is marginal for the game being hunted. Too many hunters consume, with youthful enthusiasm, the stories that a spun by “personalities” and “influencers” who are out helping to fuel the passion and dreams that fuel the industry… that’s how marketing works, folks… but it also seems to be leading hunters into something of a false reality. Simply buying gear and reading about & visualizing shooting game at long range DOES NOT grant any hunter additional skill or ability. Just like watching YouTube videos probably won’t make you an expert long range shooter… Growing up, I heard MANY deer hunters brag about how a box of ammo would last them 20 years… one shot every year… hunting on the Elkhorn River bottom of Northeast Nebraska where shots are seldom more than 50 yards…it’s not outside the realm of possibility, but it was probably a bit of a stretch. I am sure that a lot of boxes of ammo made it every bit of 5 seasons tho. Guys just didn’t seem to shoot as much back in the late 1980s and 90’s… If we transition to western hunting where shots are routinely 300 yards or beyond… it’s probably not a bad idea to get some serious trigger time before hitting the field… Equipment has improved and “ethical range” seems to have increased greatly with the equipment…but what about skill level of hunters? All the equipment in the world isn’t worth a thing if the end user does not possess the skill to use it properly. It is important to know one’s own skill level and be very honest with oneself about that skill level… anyway…back to the 243 Winchester bashing…

The 243 Winchester is far and away the most marginal – yet wildly popular – big game hunting cartridge on planet earth. Why?? Misconceptions, wives tales and great marketing… The 243 Winchester is insanely popular inspire of its actual merit. Developed in 1955 and touted as a “dual role” cartridge for both varmints and deer, the 243 Winchester became one of the most popular cartridges in the world today. Not entirely unlike McDonald’s cheeseburgers which were introduced just a few years earlier in 1948. Sure, there are TONS of better cheeseburgers based on actual merit…but volume is king…and McDonald’s sells more cheeseburgers than anyone else, so they must be the best cheeseburgers, right?…right…???? The 243 Winchester was the first cartridge advertised to really bridge the gap between varmints and medium game. Its “flat” trajectory was “perfect” for western hunting and it was more than capable enough for everything from prairie dogs to whitetail. It’s “light” recoil was just perfect for “ladies and beginners”… At least that’s what the sales & marketing goons from Winchester told the gunshop owners who helped perpetuate the 243 into the world…

Reality…well, now, that’s a little different… First off, recoil is one of the biggest hurdles for most shooters whether or not we want to admit it. We all started our shooting career somewhere. Most of us with a BB gun and/or a 22 LR. Many shooters first experience with anything that resembled recoil was probably a single shot .410. Some probably had older brothers or dad’s or uncles who thought it was “funny” to let a younger shooter try something with recoil that was far too heavy for their experience level – to “help toughen them up”…or whatever…in retrospect, subjecting beginning shooters to heavy recoil is repugnant. Recoil is just one element that reinforces a “flinch” in all shooters. Flinching makes it very difficult to hit a target. Not hitting a live target is how wounded animals happen. Muzzle blast comprises at least 50% of what most shooters would lump into the term “recoil”. Muzzle blast is concussive force created when the bullet exits the muzzle under tens of thousands of pounds of pressure that has been created by burning propellant. This pressure also adds to the “every action has an equal and opposite reaction” part of recoil as what is referred to as “rocket nozzle effect”. The 243 Winchester is nothing short of “world class” when it comes to muzzle blast, especially with lighter bullets, while actual “recoil” measured in foot-pounds may not be as heavy as something like a 308, it is comparable. However, muzzle blast takes it over the top and creates an overall more intense shooter experience. I would argue that the 243 Winchester is among the very worst cartridges to give a beginning shooter…regardless of their gender or stature…

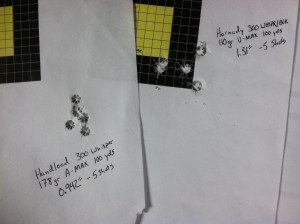

Terminal performance. “The 243 Winchester is a fast, flat shooting cartridge.” Well…by most standards, it is pretty fast. But “fast and flat shooting” is pretty misleading. For comparison, if we zero both a 243 Winchester with a 100gr bullet and a 30-06 with a 150 grain bullet at 200 yards, at 500 yards bullet drop is within a few inches of one another. If both guns shoot a 1.5” group at 100 yards, the difference in trajectory will not be noticed on the target at 500 yards as the groups will likely fall inside one another due to radial dispersion. Conversely, the 22-250 Remington with a 55 gr bullet zeroed at 200 yards drops approx 12” less at 500 yards than both of the aforementioned. The 22-250 is a significantly “flatter shooting” cartridge and therefore better for longer ranges and smaller targets – aka varmints. The 243 Winchester is fairly fast with hunting bullets, but no faster than other popular hunting cartridges like various 6.5’s, 270’s and 30 caliber cartridges, but the 243’s bullets typically weigh 30 to 100 grains less…small bullets going fast tend to tear themselves apart when they encounter the target. Larger, heavier bullets at similar speed tend to hold up better and consequently kill better. Order of magnitude matters. It’s basic physics.

The 243 Winchester is a product of marketing success backed up by large scale manufacturing and good salesmanship in the early days – just like McDonald’s cheeseburgers. The 243 Winchester is, and will always be, a marginal cartridge for big game. That does not mean that it is not a popular big game cartridge. It just means that it probably should not be a popular big game cartridge; if success is determined based on actual merit…just ask any well seasoned big game hunter who has used the 243 Winchester. Neither does the 243 Winchester offer any appreciable gain in meaningful categories over the 22-250 or 220 Swift when it comes to varmint hunting of any type. Many believe it is a good cartridge for beginners. This is also not true. Its muzzle blast is among the worst of all modern cartridges as discussed prior…beginners would be much better served by a 300 Whisper/Blackout or 7.62x39mm in a quality bolt action platform.

If you own and hunt with a 243 Winchester, that doesn’t make you a bad person or mean that that you should rush out and get a different rifle. It simply means that it might be wise to consider the actual physical limitations of the cartridge and make sure that your gun is properly zeroed with ammunition that uses a high quality bullet that will hold up to high velocity impacts and penetrate deep enough to provide an incapacitating wound to the game you will be hunting, especially if the shot angle is a little less than ideal. If one minds the details and does everything right – not forgetting that shot placement is everything – there is some margin for error, but not much. When it comes to hunting whitetail deer with the 243 Winchester. Given the number of wounded deer that I’ve personally encountered in my hunting area over the past few years, and the proliferation of hunters using the 243 Winchester in our area…my belief that the 243 Winchester is simply too small for whitetail deer…and too big to be practical for coyotes… As for it’s popularity, 1,000,000 “wrongs” don’t make a “right”…and the 243 Winchester is the perfect example of that.

So, just what would I suggest… if you want a smaller bore, short action, sure, you can get a 6.5 Creedmoor…but, if you want the best short action cartridge for hunting; get a 308 Winchester.